Tell the story…prevent a new lie — Holocaust survivor details time as a hidden Jewish child during WWII

By Wayne E. Rivet

Staff Writer

As Charles Rotmil watches television reports of Ukrainian women and children, carrying single suitcases and walking along roadways strewn with dead bodies, debris and burnt vehicles, he vividly remembers a similar time.

Charles was 6 years old when his mother quickly packed and left with her three children to escape Nazi persecution. They walked 100 miles, sleeping on hay in barns along the way, to reach a train headed for safer destinations.

“As people walked, German planes fired on us. We ran to the side of the road and jumped into the gully. I saw scene where a man and a woman were on a horse and carriage, and were killed. The horse was sliced in half. My mother tried to shield my eyes, as we walked right by them,” Charles recalled. “I had to be carried at one point. How far can I walk?”

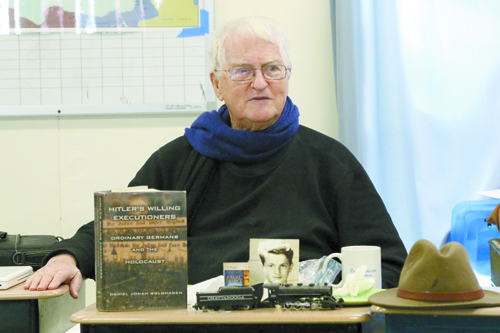

At age 89, Charles Rotmil tells his story as a hidden Jewish child during the Nazi reign of terror in Europe during WWII to provide a living history of the Holocaust, as well as providing a bold reminder to today’s youth to learn from the past to avoid history repeating itself.

Rotmil spoke to Lake Region High School Humanities class junior students last week as part of their Holocaust studies. Some 30 years ago, Alternative Ed Teacher Ann Bragdon first met Rotmil while taking a course at Bates College. He was one of the Holocaust Human Rights Commission of Maine guest speakers, along with survivor Judith Isaacson. Prior to Covid-19, Rotmil had visited Lake Region a couple of times to share his experiences.

When Bragdon started teaching in her 20s, she found just two lines in a history book that “six million Jews died in the Holocaust.”

“I didn’t think that was enough,” she said. So, she dug deeper, taking courses as well as earning a grant to visit Germany and the death camps. Today, Bragdon’s students get the full Holocaust picture from Nazi tactics, bystander apathy, the beginnings of anti-Semitism and the resistance.

“Now, which I never used to teach, we look at the before. There’s a great quote — To understand what we lost, you have to know what we had before.

What was there (before the Nazis)?” she said.

Charles Rotmil brings the words in history books to life. At first, he was hesitant to relive and recount those horrid days of his youth. In his 50s, he was convinced to speak at the University of Maine at Augusta. Little did he know, his talk was beamed across the state and New Hampshire.

He understands the importance of telling the story. Joseph Goebbels, minister of propaganda for the German Third Reich, believed that if you make a lie big enough, people will believe you. The Nazi blamed the Jews “for everything,” Charles said, “and the German people believed this” which lead to atrocities the world had never seen.

“I never asked to do this (speak). It is so important that you hear what I’ve seen. In a few years, none of us are going to be around. I was a witness, I was there. It is good for you to hear this so it doesn’t happen again. It starts with prejudice. It builds up. It is good to hear people like me talk. I represent what can happen if it gets out of control. The next thing you know there is a concentration camp, mass executions. On the Internet, there is a genocide watch. Go to it. Right now, people are being murdered because of their race or religion,” he told the students.

Charles was born on Oct. 29, 1932 in Strasbourg, France.

As a child, life was “good.” The family moved to Paris since Charles’ dad, Adolphe, was an art dealer. They relocated to Austria in 1938, but trouble immediately found the Jewish family. The Nazi seized control of the country and started persecuting Jews. Adolphe was beaten and put in prison. When he was released, the family fled to Belgium. Hitler invaded there, forcing the Rotmils to move once more.

Adolphe got separated from the rest of the family, who all got on a train.

“There were no tickets. If there was no room inside, people held on outside. I was walking in a corridor when the train hit another car. I was lifted in the air, flew and was knocked out. I woke up, covered with wood. I got out, jumped out of train, landed on man lying there who was dead,” he recalled.

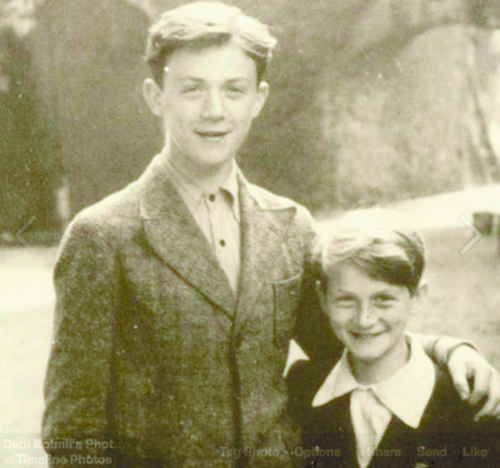

Charles found his brother, Bernard, and mother on stretchers. His sister was sitting, but had suffered a serious facial injury.Henriette died from those wounds, and Charles’ mother passed away a week later. Both were buried in unmarked graves.

“Suddenly, my brother and I were orphans,” he said. “We didn’t know where father was.”

Eventually, father and sons were reunited in Brussels. One day, Charles remembered his father returning home with yellow Stars of David that Nazis were ordering Jews to wear.

“My father refused to do it. He burned them,” he said. “That’s probably why I’m here.”

The Gestapo raided the Rotmil home. “A gun was held to my head, and they kept screaming at me, ‘Are you a Jew?’ I couldn’t talk. I couldn’t say anything. They told me to get out,” Charles remembered. “I looked out the window and saw people on trucks. Everybody was taken. You didn’t need to be an adult, they took everyone.”

In 1943, Adolphe was arrested on the street. His sons never saw him again. When Charles visited Auschwitz in his 50s, he found documentation related to his father’s arrest and transport to “termination camp.” His father was prisoner number 779 on the 21st train from Malines prison in Belgium to Auschwitz in Poland, where it arrived on Aug. 2, 1943. There were 1,536 people on the train. The record included a notation, “Gas Upon Arrival.”

“I told a worker there I was coming to my father’s grave. You walk on the ground and you don’t know what you are walking on. There are ashes. It is very ominous. I wanted to go to the spot where the gas was. I did that at one point. I tried to imagine what it must have been liked for my father,” he said.

A neighbor told Charles and Bernard they better go into hiding. “They will come for you next, you can’t stay in your apartment.”

Bernard sought help. He found Father Bruno Reynders, a Benedictine monk who hid and saved an estimated 350 to 400 children during the course of the war. Father Bruno placed Charles and Bernard with different “safe” families. Charles went to Catholic school, and even became an altar boy.

“I loved to swing the incense. I’d see Gestapo agents sitting in the pews, praying and thinking, ‘see that cute little boy at the altar.’ Little did they know I was Jewish,” he said. “I’d push the incense smoke into the Gestapo faces.”

To this day, Charles still “loves the smell of incense.”

One advantage, Charles believes he had, was he didn’t “look like a Jew.” He had blue eyes and had blonde hair. He pointed out to students that the Germans created a stereotype of “what Jew looks like — crooked, big nose, ears sticking out.” “People believed it,” he added.

When the war ended, Bernard and Charles contemplated leaving Europe and moving to Palestine. But, they changed course when they saw an advertisement in a newspaper, placed by their aunt and uncle in America, seeking Rotmil family members.

Bernard headed to New York on a Liberty ship, while Charles ventured across the sea on an ocean liner, since he was too young to travel on the Liberty.

A favorite story he likes to tell is about a stop in Liverpool, England.

“We were taken to a shoe factory and each of us were given a new pair of leather shoes. I didn’t wear them. I put them in my suitcase. I wanted to wear them when I stepped into the new world. When I got to New York, I put them on. I wanted to step into the new world in new shoes. It was amazing,” he said.

Charles arrived in the United States at the age of 14. He went to Temple University. Married. Had three children. He left New York in 1982, and came to Maine, settling in Damariscotta. Charles first worked in the nursing field, but then became a foreign language teacher. He enjoys playing chess and performs old-time German melodies on a harmonica — one of which he was given as a child during wartime. He plays it as part of his speaking engagements (“Before, I couldn’t play in public, because I wasn’t supposed to draw attention to me because I wasn’t supposed to be there; I didn’t exist,” he said). Charles likes adventures, pointing out he hitchhiked to Mexico. “I don’t recommend doing it,” he added. He also has a great sense of humor.

His brother, Bernie, worked for IBM. He passed away at the age of 82.

“We liked to compete. I am winning on longevity,” said Charles. “I don’t plan to die, I’m against the idea. When you are dead, you don’t know it.But when you are alive, it really bothers you.”

One question that often arises is whether hidden children are considered Holocaust survivors? Charles once had dinner with Elie Wiesel, a champion of human rights and Holocaust survivor, who said,“You’re a survivor, your family was murdered and you were forced in to hiding. You’re a survivor.”