In Ye Olden Times: The case of Bridgton’s stolen Boston Post Cane

By Michael Davis

Guest Columnist

Howdy neighbor!

In our last issue, I was pleased to see featured as a front-page story the recent transferal of the town of Brownfield’s Boston Post Cane to Mrs. Della Smith, who at 95 years of age is the oldest legal citizen of that town. And as this story involves the history and custom of the Boston Post Cane, I thought it well to devote this column to the local story of that venerable New England tradition, first started back in 1909 by the Boston Post newspaper as a joint advertising stunt and note of thanks to their wide readership in rural, small-town communities like ours.

Starting in 1909, the editor of the Boston Post forwarded a series of gold headed, ebony walking canes to the selectmen of 700 small towns in Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, with instructions that they be bestowed by each town as gifts to their oldest male citizens, thereafter to be handed down consecutively upon the death of each recipient to the new oldest man, for all the years of American Independence yet to come. As the Bridgton News once observed of this tradition; “The Boston Post Cane is forever being passed on.”

Cities were expressly excluded from the program, much to their chagrin and the wide pleasure of we country folk, but as an interesting note in Maine’s history it somehow happened that Hallowell received a cane too, despite its officially being a city by charter and having a mayor instead of select board. Though a very small city at just over 1,000 citizens, it remains to my knowledge the only legal city in all New England to ever receive one.

Apparently, Vermont and Connecticut were also excluded from the program, and while I don’t know why, a friend of mine from Vermont informs me that there were once two towns in that state who somehow got their hands on a Boston Post Cane, and so took up the tradition unofficially in the Green Mountains.

But by far the most notable quirk of this program, and one which the editors staunchly defended for decades, was the proviso that the cane could only be lawfully bestowed upon the oldest male citizen; a distinction rooted in the idea that it could only be handed down to legal voters in any municipality. Of course, after universal suffrage and the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920, women began to request inclusion, but it took another decade until, with some grudging, the Post relented and at last allowed their qualification for the honor in 1930. And so today in Brownfield, Mrs. Della Smith takes home the gold, and I can only say, long may she enjoy it!

Beyond Brownfield, this tradition is still carried out locally in Harrison, Otisfield, Sebago, Raymond, Fryeburg, and Denmark, (I hope I didn’t miss anyone) and in all there remain 546 towns of the original 700 who still pass on the Boston Post Cane today.

Sadly, Bridgton is no longer one of them. So, seeing as I have made the study of our cane’s convoluted history a point of personal interest and done much research upon the subject on behalf of the town, I think now is a good time to bring its history forward. I begin with the text of that letter received by the Selectmen of Bridgton from the Boston Post, dated August 2, 1909;

“Dear Sir: We take the liberty of requesting of you and other members of the Board of Selectmen of your town a little favor, which we trust you may be able to grant. The Boston Post desires to present, with its complements, to the Oldest Male Citizen of your town, a gold headed cane, and as you are doubtless well-informed as to the citizens of your town, we ask that you make the selection and presentation.

The cane is a fine one, manufactured especially for this purpose, by J.F. Fradley & Co., of New York, who are generally recognized as the leading manufacturers of fine canes in this country. The stick is of carefully selected Gaboon ebony from the Congo, Africa, and the head is made of rolled gold of 14 karat fineness. The head of the cane is artistically engraved, as presented by the Boston Post to the Oldest Citizen of your town (to be transmitted.) The idea is that the cane shall always be owned and carried by the Oldest Male Citizen of your town, and upon the decease of the present Oldest Citizen, remaining always in the possession of whoever is the Oldest Citizen of your town. Upon the head of the cane a blank space has been left where the name of the owner may be engraved locally, if desired.

We request that in an informal way your Board act as trustee of the cane and see that the stick is duly presented and duly transmitted when such a change of holders becomes necessary. We do not suggest any formal trust or any legal or financial responsibility on your part, but simply that you act in the matter in accordance with the plan outlined as your best judgement indicates. There is no charge whatever by the Post to your Board, or to the holder of the cane. In case your Board will undertake to act for us as suggested, we would request that you notify us to that effect, a directed envelope being enclosed.

Very respectfully yours, A.E. Grozier, Editor and Publisher.”

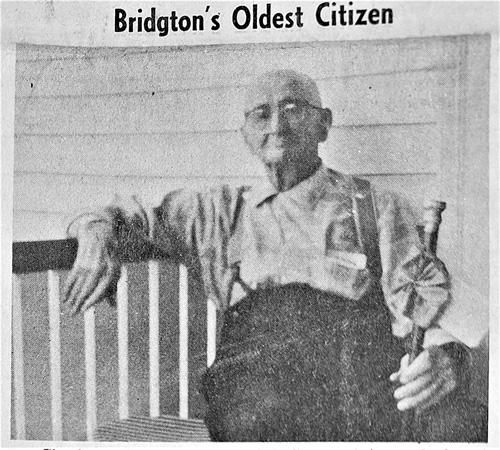

At once accepting this honor and the cane which came with it, Bridgton’s selectmen canvased the voter rolls and found our oldest male citizen, Mr. Samuel F. Kilborn of South Bridgton, who at 88 years old was promptly notified and gifted his cane on Sept. 8. He would faithfully bear this honor until his death in May of 1912, at which time the cane passed on to Charles M. Staples, thus beginning a chain of transmission which would take the cane through over a dozen hands for some fifty years. The founder of the Bridgton Historical Society, Blynn Davis, once lamented that no list had ever been complied of all of Bridgton’s cane holders. Looking to set right that injustice, with the aid of the archives of the Bridgton News and certain documents now on file in the society’s archives, I have been enabled to prepare such a list, as follows: 1909-1912, Samuel F. Kilborn; 1912–1917, Charles M. Staples; 1917–1920, George W. Hilton; 1920–1924, George W. McGee; 1924–1927, George F. Knapp; 1927–1929, Elkanah A. Littlefield; 1929–1930, Joseph E. Gammon; 1930–1936, Albert B. Kilborn; 1936–1938, Gardner F. Chase; 1938–1949, George W. Rounds; 1949, Eugene H. Tenney.

This brings us to 1949 when it passed to 91-year-old Eugene H. Tenney upon the death of Deacon George Rounds, who had received it in 1938 at 89 years old and held on to it for more than a decade, until his death as a centenarian at 100 years of age! Unfortunately, at the time Mr. Tenney received it, he was in hospice care, as noted in the News of Sept. 2, and just a week later, the News of Sept. 9 ran his obituary. I expect he had it about a week, which as a point of fact is the shortest term anyone in Bridgton ever held the cane. Reflecting back on the intervening period, another worthy event which I should mention is how in 1930, when Albert B. Kilborn received the cane in October, he with much good humor exchanged his own silver headed oak cane with the selectmen, taking the Post cane to replace it and telling them that they ought to give his silver cane to the runner-up in perpetuity, ‘so that the second oldest man in town might have something to lean on while waiting for the oldest gentleman to die.’ This cane was duly handed down as well, though records of its transmission are spotty.

Returning to the history of the Post cane in 1949, with the sudden death of Mr. Tenney the selectmen turned to their registries and found the gold cane’s next recipient should be a man named Charles H. Mackay, and it is here that the clean transmission of the cane breaks down.

Now, Mr. Mackay is an interesting figure, who I believe I have mentioned before in this column. It is likely that one day I will devote a whole feature to him, but for now I shall summarize. Many were his honors in life; An expert cornet player, venerable member of the Bridgton Band, composer of a state ballad, accomplished letterpress printer, seasoned railroad station man, amateur archeologist and trained astronomer. He also dabbled in astrology, told fortunes and ran a mail-order clairvoyance class, sitting as head of a mystic secret society of over 500 members, which he dubbed the West Gate Brotherhood, whose newsletter and lodge rituals he published right here in Bridgton in a monthly metaphysical paper, The Oracle. Some of these are on file at the Historical Society. He once gave an interview on the subject, which I hope to do more with one day, but for now it will suffice to say that in September of 1949 he became the recipient of a further honor: The Boston Post Cane.

And what do you know — he refused it! I have no idea why. Whatever his reasons, rooted in whatever sort of motivations, he flatly declined the honor and in so doing left the selectmen wholly without recourse for what to do next. No one had ever done that before, and yet the Post’s rules were quite plain that only the oldest man should receive the cane. Since they were already giving the Kilborn silver cane to the second oldest citizen, there seemed no one else fit to take it at that time, so instead the cane was dutifully filed away in the Town Vault. It is likely that at this time someone fully intended on carting it out and giving it to the new oldest man whenever Mr. Mackay died, but when that finally happened in 1953, no one did. Though only four years had passed, the chain of transmission had been broken, and with the cane not out in circulation no one seemingly remembered the duty. That is until 1968 when, in preparation for the Bridgton Bicentennial, the cane was re-discovered and, as part of the celebrations, solemnly bestowed to the 93-year-old George H. Kilborn on Old Timers Day. It is an extraordinary genealogical testament to the Kilborn family, that George’s father Arthur had held the cane 38 years before him, as had Arthur’s father Samuel, who had been the first to receive it! That’s no less than three generations of Kilborn’s standing as the oldest citizens in Bridgton in their day. This final Mr. Kilborn held it until his death in 1969, at which time it passed again to Charles B. Bailey, who kept it until his death on Oct. 12, 1974.

That, dear readers, is to my knowledge the last time Bridgton’s Boston Post cane was ever given out. Returned to the Town Office by Bailey’s family, it was again put in storage, together with the Kilborn silver cane, whose transmission I cannot trace after 1953. Sometime in the 1990s, it was placed in a locked glass case in the lobby of the Town Office as part of a display managed by the Bridgton Lions Club. But sadly, it is not there today, for as The News of Nov. 23, 1995 reports, in early November it was discovered by town clerks that the cane, quite without anyone’s notice, had been stolen by a wicked vandal who had surreptitiously broken the lock and spirited the cane away sometime in the two months before the robbery was discovered. The thief’s identity was never established, and so a vital piece of our cultural history remains lost to us today.

But how good it would be for this tradition to be revived? I have spoken in past years with some at the town office who have an interest in seeing it return, but the pandemic shelved those talks and they have not yet resumed. I must confess a big part of my writing this column, is to highlight the present situation to see if our readers feel as I do, and if so, to relight the fires under this issue. As I am now the chair of the town Arts and Culture Committee, assistant director at the Historical Society, and history columnist here at The News, I feel a particular obligation to do what I can toward the maintenance of our traditions, and this issue is just about next on my list now that we’ve succeeded in returning the candlelight processional to the Festival of Lights. (My sincere thanks to the 18 people who walked with us this year, and to all the folks who gathered along the parade route with candles in support of us!)

Of course, a replacement cane could likely be procured; there is actually still a system in place for those towns whose canes have been lost, broken, burned, or otherwise destroyed, and all you have to do is prove your town originally had one — cities are of course still rejected on moral principle — but for me I feel it would be a far better thing for our town to regain our lost original. Perhaps it is lost irretrievably; pawned, sold, its inscription sanded down, the head melted for the gold value… but I hold out hope that it does still exist, that it is still out there, and that possibly it is still in local or at least nearly local hands here in the State of Maine. Unless of course, Vermont got it... Does anyone really know how those two towns got theirs? It might bear looking into...

Speaking seriously, I am here putting out a call and cry on this cold case and can only say that if anyone out there knows its whereabouts, I would be perfectly happy to see it turn up on the doorstep one day, no questions asked. I am only interested in the return of this local treasure, not in pressing any old crime beyond the statute of limitations; it matters not to me who had it or why, and anonymity is fine with me. If anyone out there does have it, or perhaps inherited some old gold cane with the name Bridgton on it from a deceased relative or shady uncle who said he was given it for such and such a reason, I would urge you on behalf of my hometown and the history of a place I love so very dearly, to do the right thing and return it. Because unless you’re the oldest person here in Bridgton, it really doesn’t belong to you.

Till next time!

Michael Davis of Bridgton is the assistant executive director of the Bridgton Historical Society.