Future builders tour home of the future

NET ZERO’S NEXT GENERATION — Students and teachers from the Lake Region Vocational Center gather in front of Justin McIver’s “net-zero energy†home in Sweden. Attached to the south-facing roof can be seen the bank of 39 solar panels which, combined with the home’s super-energy-efficient construction, allows the home to produce as much energy as it consumes annually. Posing with the students are McIver, his project manager Dave Giasson, drafting and design teacher Sally Thompson and construction technology teacher David Leddy.

By Gail Geraghty

Staff Writer

SWEDEN — When he began Main Eco Homes in Bridgton in 2008, Justin McIver realized that education, of necessity, was going to be a huge part of his mission.

The young entrepreneur is a homebuilder whose has taken the concept of “going green†to the absolute limit, by building the first “net zero†home in western Maine. It’s a home that is so insulated and energy-efficient, it doesn’t need to rely on fossil fuels. In fact, on an annual basis, the home doesn’t cost anything to heat, because it’s designed to produce as much energy as it consumes.

“Why build a house that uses low energy when you can build a house that uses no energy?†McIver said.

Now 98% completed, the 2,000-square-foot home is on the market for $419,000. But until it sells, he is treating it much like a model home, offering tours to vocational students from Lake Region High School and Fryeburg Academy.

McIver’s first test as a teacher came on a brisk November morning, when a school bus climbed up Black Mountain Road in Sweden and stopped at the net zero home on Woodbury Hill, a small subdivision of newer homes. A class of around 20 LRHS entry-level building trades students climbed out.

After giving the teens and their teachers, Sally Thompson and David Leddy, time to admire the stunning Mount Washington views, McIver and his Project Manager David Giasson got down to business.

“This is the home of the future,†he told them, gesturing to the two-story open concept home, its south-facing roof blanketed by a veritable army of 39 solar panels. He spent three years simply designing the home before he even began to build, relying on the Home Energy Rating System Index to design every square inch for maximum efficiency. The HERS index determines how many BTUs the house will use on an annual basis.

McIver has built many energy-efficient homes before, but with this one he wanted to seal it as tight as a drum. This he achieved, through the use of triple-pane windows and walls that measure over 10 inches thick, compared to the standard six inches. The home is ranked among the top 3% in terms of insulation in the country.

There’s two inches of rigid foam board on the outside over 2 inch by 8 inch studs to keep cold from coming in through the wood; and on the inside, the insulation consists of spray foam made from recycled bottles. As if that’s not enough, every crack and cranny around windows and seams is packed in with blown-in cellulose made from recycled newspapers and blue jeans.

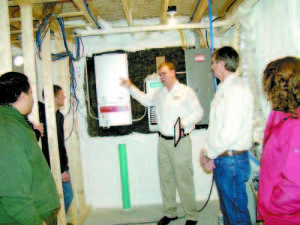

POWER PAYBACK — Justin McIver points to the power control center in the net zero home, explaining how it monitors the home’s use of solar power for heating and electricity.

“In Maine 58% of your utility costs comes from heating,†McIver said. “You get the most for your money from insulation.†When you combine super-insulation with efficient design and a large solar array, he said, “You can heat this house with a hair dryer, almost.â€

The home is all electric, and will generate enough extra solar power in the summer that it can be sold back to Central Maine Power in the winter, thereby achieving zero energy costs to the homeowner. In the open concept living area, McIver pointed to a small electric heater mounted high on a side wall. “One electric heater on the wall heats this whole house.â€

McIver said the average monthly electricity cost in the net zero home, for both heat and lighting, will be about $50.

At age 30, McIver showed he hadn’t lost his sense of wonder as he described the potential of solar power as an alternative to oil and other fossil fuels. “Every day, the sun can meet the whole energy demand of the world,†even in its dilute form, with today’s advanced solar technology, which costs roughly half as much as it did five years ago. He said it’s a myth that Maine isn’t a good location for solar power. Germany relies heavily on solar power, and that country receives 30% less sun than Maine does, he said.

In the basement, the students could see enough of the framing behind the walls to begin to appreciate what super-insulation is all about. Since every seam is a place where heat can be lost, the framing is 24 inches on center instead of the standard 16 inches on center. An iron support beam supports the first floor from one end of the house to the other, eliminating the need for cellar support posts and allowing for better airflow.

The entire home is also served by a ventilation system allowing for the exchange of fresh air. “You’ve got to let it breathe,†McIver told the students, lest moisture get trapped in such a tightly insulated home.

McIver said he’s planning to build less expensive net zero energy homes in Raymond, to counter any belief that only the well off can afford to own such a super-efficient home.

“I want to lead and create this movement,†he said. “My dream is to do a whole community of these homes.â€