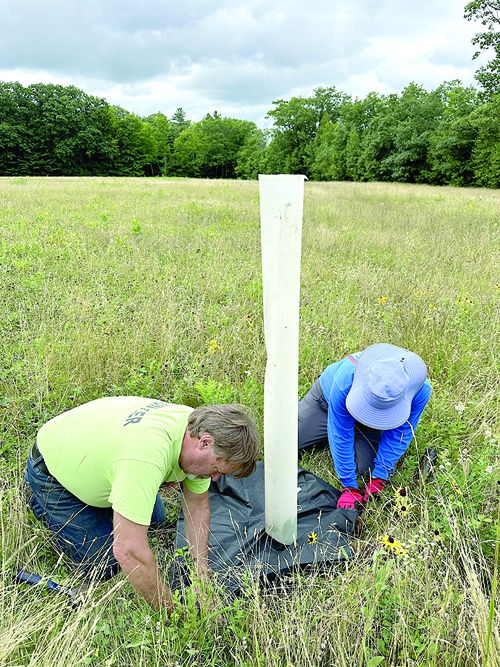

Endangered chestnut trees planted on LELT lands

(Photo courtesy of Loon Echo Land Trust)

By Dawn De Busk

Staff Writer

The simple act of planting a sapling represented not only the future, but also a year of labor-intensive, detailed volunteer work in 2023 for Kim Colson.

The tree was the American Chestnut, which was wiped out by the chestnut blight in the 1930s. This July, Colson and Loon Echo Land Trust (LELT) Stewardship Manager Jon Evans put six saplings into the earth at Peabody-Fitch Woods Preserve.

“It was really exciting. Jon picked where the row of trees was going to be. He picked a place that has such prominence for a once majestic tree. He is giving it a prime location to grow. These specific trees might not succeed in the long-term. At some point, we will have a tree that will survive in that location,” Colson said.

“These trees grow really fast. When they grow, they grow really straight and really fast. They are remarkable,” the Sebago resident said.

Colson heard the sorrowful tale of the American chestnut tree for the first time when she was a young girl.

“I first learned about the American chestnut tree when I was a kid. A friend of our family, Jeff Smith, was a prominent forester in New Hampshire when I was growing up,” she said. “He told us how this huge tree all of sudden died. He harvested the wood to get rid of it. It was just a beautiful, beautiful tree and he missed it so much.”

“Then, about 25 years ago, I heard a presentation on it by a fellow out of the New Hampshire chapter of the American Chestnut Foundation (ACF). He said there was an effort going on to restore it,” Colson said. “I was ecstatic. This tree that I heard about and will never see again has the potential of being restored.”

(Photo courtesy of Loon Echo Land Trust)

She was so moved by the prospect that she signed up to volunteer with ACF. Also, she started volunteering in orchards in Maine that are used for test purposes for restoration plantings, and she has been involved ever since.

This summer, LELT became part of the ACF’s pilot program to plant chestnuts on public lands.

Earlier this month, a documentary on the American chestnut tree called Clear Day Thunder was shown at the Magic Lantern Theater.

The title comes from the description of people who were alive when the trees were destroyed from the blight within a year or two. The forests were filled with dead-standing trees, which would fall sporadically and it sounded like thunder.

An inspirational movie, a movement

Following the documentary, some of the people involved in chestnut restoration spoke.

Eva Butler, Vice President of the Maine Chapter of the ACF, who is also the founder of the Chestnuts Across Maine (CAM) project, asked the crowd if they felt inspired by the documentary. The response was yes.

“I’m delighted to see you all here because

Healthy forests — Restoring the American chestnut will improve our forests and increase biodiversity.

Restoring an American legacy — Referred to as the “cradle-to-grave tree” for its variety of uses [cradles, cribs, caskets, coffins] it was an important food source and cash crop for the people of Appalachia.

Superior wildlife food— A single American chestnut tree produces abundant and highly nutritious food for wildlife year after year.

Reclamation — Its fast growth and tolerance of rock, acidic and poor soils makes it perfect for returning degraded landscapes, such as those left by mining, to diverse and healthy forests.

Road map for the future — American chestnut research creates a template for restoration of other species across the world.

Outstanding timber — The lumber is straight, strong and rot-resistant.

Craftsmanship — A light, durable wood with a lovely color and attractive grain appreciated for furniture and architectural elements.

Cuisine — The seed is smaller and sweeter than other chestnuts. It is often preferred for cooking and roasting because of its superior flavor.

Landscaping — The American chestnut spread its branches wide as a shade tree and produces large white flower before its abundant fruit production.

Conservation — Restoring the American chestnut will be a conservation achievement of historic proportions, turning around what is considered to be one of the worst ecological disasters of the 20th century.

Reprinted from the American Chestnut Foundation

I am an evangelist for chestnuts,” Butler said. “I have been a member for slightly less than four years. When I was a volunteer coordinator, I discovered we have chestnut orchards that have been developed by this chapter for the past 26 years.”

She visualized a solution after talking to a 91-year-old ACF member who did the mapping of trees.

“He asked me, ‘Why do we keep building an orchard for gene conservation and planting these trees, which will die. If one or two trees gets blight, within two or three years they all have it.’ It rang a bell in my head. I thought, ‘So, we need to get chestnuts closer to our people. We need to get them spread around so that doesn’t happen,’” she said. “The Chestnuts Across Maine project was born out of need to 1.) Conserve the genes we have; 2.) Be able to take new combinations we are researching and get them into the forest; and 3.) If we have a blight-resistant tree today, have people standing by ready to plant them,” she said.

“If we had it [a blight-resident tree] today, the question is: how would we restore the forest? How would we plant out a million trees? It is not a government project, county extension is not going to do it. It’s is going to be people-powered like everything else really matters,” she said. “If we could build a program and give people access to trees that they could plant, you would build a little community around chestnuts where you live so when those trees that have resistance become available, we have communities across the state, people who can get them into the ground.”

“I think that the passion that comes from community connection. Around this country, what we need more than anything is community and connection. The chestnut, from my experience in four small years, is an incredible agent for connection. Through it, I have met the most wonderful people and been so inspired,” Butler concluded.

Hopeful year ends in disappointment

Kim Colson, who was instrumental in doing the networking needed to bring Clear Day Thunder to the Magic Lantern in Bridgton, spent a year in 2023 preparing other volunteers for a blight-resistant chestnut tree that never materialized. Faulty research was to blame. However, it proved to her how people will rally around an environmental cause.

It sent everyone in the right direction, which was keeping it local. ACF members in New England chapters realized it would be more effective to start small and reduce the amount of travelling volunteers were doing.

“We wanted everyone to be able to go to see the trees. When I was thinking where to go, LELT was the first to come to mind. I had volunteered there before; they have lots of land; the people are great,” she said.

She described the previous year’s endeavors.

“Last year, in 2023, all year long, we were expecting a number of government agencies, the EPA, the USDA, in determining whether a transgenetic project could be released or not. They had a tree that they thought was blight resistant. In the orchard in New Hampshire, I was training volunteers how to pollinate, how to monitor the trees. The problem with a transgenetic tree, it has 100% of the same DNA. A particular tree is not going to be robust against disease as other plants. It doesn’t have the diversity of DNA. The plan to introduce the transgenetic tree to pollinate with as many trees as we could so it would have a more robust DNA set. We wanted controlled pollination of it, to make sure it cross-pollinates with the American chestnut and not the Chinese chestnut. As 2023 was unfolding, we were working hard to prepare people so we could be ready for cross-polination of the transgentic tree as soon as possible,” Colson said.

Volunteers were trained via two Zoom sessions plus an on-site visit.

“The pollination isn’t that easy. The catkins (the male components) come out first; then the females buds come out. You have to make sure the female buds don’t get pollinated by something random. We want tree that have greater blight resistant. To actually do the pollination of it, we had to have a group of volunteers who knew how to observe the bud and know when it is within a couple days of being pollinated. I needed people go out to the orchard every day, and say, ‘This tree is getting close.’ They had to review all 150 of the trees in that orchard in terms of bud development,” she said.

Additionally, after pollination, each bud is covered with a bag to protect it from random pollination. The bag remains on the bud until the nut forms.

“When it looked like we had some trees that were ready to go, we had to coordinated a bucket truck from the local utility company,” she said.

They discovered utility companies were more than happy to help, to donate the use of a bucket truck and operator for this purpose, Colson said.

Other threats to Maine trees

After the documentary, Loon Echo Land Trust (LELT) Executive Director Matt Markot bounced off Butler’s comments about the power of community in the success.

“Talking about community. We have such an incredible community here in the Lake Region that has very strong connections to our natural land here,” he said.

“Some of you in this room probably remember or have family members who responded to the pine blister rust more than a half century ago,” Markot said, crediting those people to saving the white pines.

“We have a community that is ready, willing and able to respond to these types of crisis,” he said.

There is good news about trees that have survived blight-free in Maine. There are

wild American chestnuts growing on preserves in the region.

“The chestnut is not the only tree that is struggling in Maine. Emerald ash borer is devasting our ash trees. We could expect to lose all of our ash trees here. Of course, the American Elm succumbed to Dutch elm disease. Because Maine has geographical isolation, we do have wild elm trees growing,” Markot said. “Emerging threats to our forest ecosystem are not over. Currently, Maine is dealing with a new threat, which is beech leaf disease, which has the potential to devastate a mass-producing tree, the beech tree. I don’t expect that to be the last threat to our forests. We need a community of people who care about these trees, about our ecosystem.”

“I wanted to leave you with this: we think about the lands we conserve from the prospective of how it is serving all of you,” he said. “We want our lands to be used as laboratories for this type of work so 100 years from now, American Chestnut trees are growing in the Lake Region and the next generation of ash trees are growing here in the Lake Region and who knows what else.”