Bob Carlson — Tale of a tail gunner

By Dawn De Busk

Staff Writer

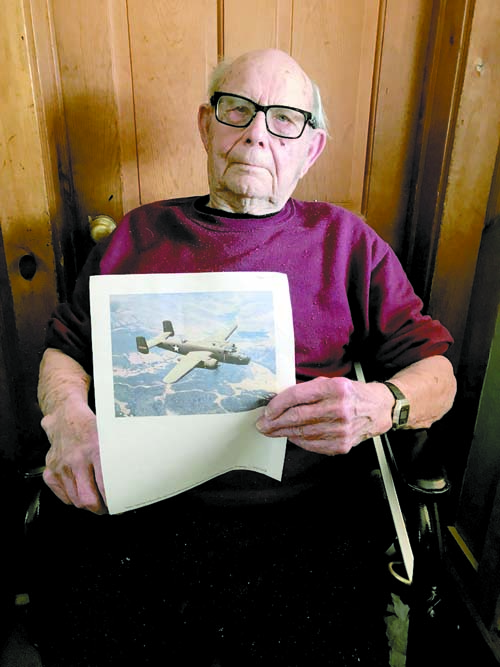

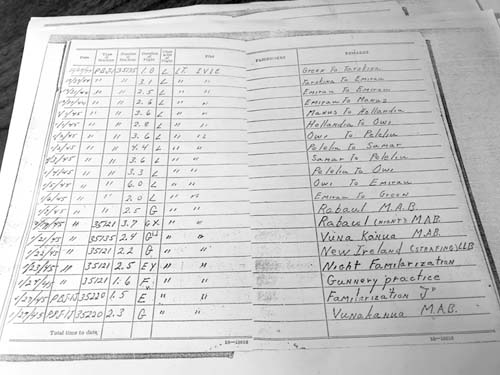

HARRISON — Bob Carlson has a record of every flight he took from his time as a tail gunner on a B-25 in the South Pacific during World War II.

He referred to his log book and a world map as he talked about his experiences serving in the Marine Corp’s aviation division from 1943 until 1945 when the war ended.

His job was not one that people coveted. Carlson was a tail gunner on a bomber plane. Each plane had a crew of seven including the pilot. Carlson sat in the very cramped end of the plane surrounded by ammunition.

The models of planes weren’t luxurious like the commercial ones today, he said. The planes were pretty primitive 70 year ago, he said.

“The planes were completely stripped of all air conditioning or any insulation at all. When you got into the plane, it was like getting into an aluminum tube. The sweat would be pouring off you, and you’d freeze,” he said. “I was on my knees on a bicycle seat that was underneath my butt. I was on my knees all the time. Sometimes, it made it difficultto crawl out to get back into hatch again.”

It was an ordeal getting into position in the first place, he said.

“To get in there, there is a hatch underneath. You crawled into it and left your parachute behind. You had ammunition on both sides of you. Once you got in it, you weren’t going to get out until the flight was over. There was no way to get out if the plane got damaged,” he said.

At 96 years old, Carlson has the distinction of being the oldest World War II veteran in the Town of Harrison. Given his job as a tail gunner, just staying alive was either an amazing feat or a luck of the draw or both. After all, the statistics from WWII show that coming out alive was not favorable for the men aboard those bombers.

“During the whole war, 51% of aircrew were killed in operations, 12% were killed or wounded in non-operations accidents and 13% became prisoners of war,” according the Imperial War Museum(IWM).

“Only 24% [of air crew] survived the war unscathed,” according to IWM’s article Life and Death in Bomber Command.

“The average death rate of a WWII gunner is 46%. Out of 125,000 aircrews with gunners, more than 57,000 were killed in action,” according to Wikipedia.

Surviving A Close Call

Carlson described one brush with death.

“Coming home from a mission, the pilot called me and he said that the front wheel was leaking hydraulic oil and he wasn’t sure if it was going to last when he lowered it. He said for me to stay in my position. Don’t leave. He wanted to save the engines so he was landing on the tail. The crew was told anything that is loose put it in the tail,” he said.

The space around him got tighter. More explosive material was packed into the plane’s tail as the crew prepared for impact.

“I was getting a little bit, well, damn concerned at the time,” Carlson said. “Usually, a plane doesn’t leak. Oil started to come in and it soaked me with oil. I was right where I couldn’t do a damn thing. I was packed with ammunition.”

“I had a pistol. The military gave it to us for something like getting shot down or getting captured by the Japanese. It was easier to put a pistol right under the chin and pull the trigger than to die like that. If was going up in smoke, I wasn’t going to burn to death and I was going to shoot myself,” he said.

“The front wheel locked,” and he walked away from what seemed like it would be an injurious landing.

“I didn’t even go to debriefing when it landed. I just went back to my tent. This time, I had very little religion left. Where do we go from here?”

Many years after the war ended, Carlson purchased the home that had belonged to his family. It is the same home in Harrison where he had been born in January 1926.

He found healing from the war by repairing the house and working the land, he said.

“I think it was the best therapy I could ever have,” he said.

Enlisting and Going Overseas

Carlson was 15 years old on Dec. 7, 1941, when the Japanese military attacked the U.S. military base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Shortly thereafter, America entered the war.

Carlson was too young to serve when the war began. He recalls farmers saving metal for the war effort.

Carlson enlisted in 1943. He trained at Parris Island, S.C., before being shipped to the South Pacific islands near Australia.

“I had quit school at the time. I heard if you don’t go in the service and the war is lost, you have gained nothing,” he said.

He took a trip to Augusta to enlist.

“I enlisted at 17. After my training, I went to mechanic school. I was at the head of my class. The base wanted me to go to mechanic instructor school. I was so young, and I thought I would have a hell of a time teaching people so much older than me. So I decided not to do that,” he said.

His older brother Bill had enlisted before he did. He joined the Army as a navigator on the B-29.

Carlson describes his trip from the United States to the South Pacific islands, where there was a lot of action during the latter half of the war.

“I left California on the U.S. Munda, a baby flattop carrier. It was on a shake-down cruise to see how it would perform while it was running. Around 18 knots, it shook like hell, Apparently, it went all right. It did have its issues in that they were working on it all the time. The new crew was as green as I was,” Carlson said. “It was loaded with F-6 fighters. They could start some of them. Below the deck, they had as many planes as could get in the thing. Going over there, we slept under the planes. We didn’t have anything other than our mattress.”

The U.S. Munda managed to get the marines and the planes to the destination.

“We ended up in Espiritu Santo Island,” he said. “We got on a ship totally covered with rust. It was covered with derricks on it, cranes on it. It followed the coast. It was an old ship that was originally on coal and was converted to oil. One that you couldn’t sit down to eat a meal. You had to stand up, rails around the table. They had canvas bunks, anywhere from four to five high,” he said.

Carlson spent about eight (8) days being transported on the ship.

“I could look over the back end and see the propeller moving very slowly. The Japanese would have never wasted a shell on that one,” he said.

“We were replacements. We were sent to the Island of Emirau,” he said.

He learned about the coast watchers.

“They were single people who stayed on the island and had most of the communication by radio. They were Australia’s military. If the Japanese caught one of them, they were tortured to death. They were doing quite a service. Their job was to tell where the action was happening. They were on the islands and communicated with radio. They couldn’t build a fire or anything because smoke would show Japanese where they were,” he said.

The American air crews relied on the information gathered by the coast watchers to head to where the action was.

“We stayed very close to the enemy,” he said.

According to his log books, he went on daily bomber flights from Dec. 29, 1944, through Jan. 7, 1945. He served on 42 bomber trips during the first four months of 1945, from January through April.

The conditions outside of the bomber were inhospitable.

“We slept in four-man tents under mosquito netting. Our clothes would mold very quickly. It was very damp conditions,” he said.

In fact, flashlights were rendered useless because the humidity would quickly ruin the batteries, he said.

“The worse place I’ve seen, the shortest bombing, was Bloody Nose Ridge. They were loading bombs on one end of the runway, and bombing the other end of it,” he said.

“All of it was quite a change from the little town of Harrison,” he said.

“At the Island of Samar, we had three F-4 fighters following us. When we started on the run, we were supposed to go to a different place” than where they took off originally. The crew landed at Samar at the same time that an airstrip was being built by the U.S. Construction Battalion.

“The Construction Battalion was made up of men who were contractors. I assume they landed by boat to get the equipment off. They made us an airstrip. The fighter planes could land easy. They had to pack it down some, so a twin-engine bomber could land,” Carlson said.

“We landed but couldn’t take off. By 11 o’clock the next day, we were able to take off,” he said.

World War II Ends

“When Roosevelt died it shook us up quite a bit. Then Truman took over. The atomic bomb was dropped and that stopped everything,” he said.

Despite having served in a tough job, Carlson said many Americans serving in the war had it harder and also other people deserved credit.

He does not envy the military personnel who served as foot soldiers.

“Those fellows what was so hard for them is if you are near a place where there is a lot of action, the screaming of people at night that they couldn’t help. I was lucky I never had to get into that at all. Because flying, I usually had a good place to sleep. The infantry, the ground troops — they had it hard,” he said.

“The people you don’t give credit to at all are the ones that were feeding us,” he said.

“We always got feed. They had the K-rations. It was just like a Cracker Jacks box. It had canned meat, canned cheese spread, a couple of hard crackers, a couple of cigarettes and instant coffee. It wasn’t very instant, especially in cold water. All our food was dehydrated. There was nothing frozen back then. It was all dehydrated,” he said.

“I think the ones that are feeding us did an exceptional job. They had to be there at different times,” he said.

When the war ended, Carlson traveled back to America on a hospital ship. He was discharged in August 1945.

When he initially returned home, he worked for a construction company, but that job ended.

“Then, I had the chance of going on unemployment for $20 a week. I was very much against unemployment. I didn’t believe there was any need to go on unemployment,” he said. “I took a job for $20 a week plus room and board at Thomes Farm,” which was right on Maple Ridge Road in Harrison.

He wanted to marry his sweetheart but had to wait until he was making more money to support a family, he said.

Later, Maine Machine Products in South Paris hired Carlson. He rose to the position of production supervisor; and that was the job from which he retired.

Decades after the war, he ran across discarded military planes and took a trip down memory lane.

“One the thing that is so interesting when I was in Memphis, Tennessee, there was a military airplane dump. As they got old and no longer used, that’s where they got rid of them,” he said. “I was interested in the interior. I went into a lot of them. The drugs that were used in first aid kits. They were all intact. None of them had been touched. It kind of surprised me.”