In Ye Olden Times: When a million Ouija boards were produced in Bridgton

By Mike Davis

BN Columnist

Howdy neighbor!

It’s time for our annual Hallowe’en treat! The one time a year when I can cast off the rigors of strict historical documentation and instead revel in the wealth of vague folklore, doubtful witchcraft, and good old-fashioned ghost stories in which New England abounds, and of which Bridgton has likewise its treasured share.

We’ve had beasts, and ghosts, and curses too… that is if you trust the old-timers who’ll tell you so with a wink and a nod. Every year at this time, I do my part in perpetuating the cultural memory of all those things which, at one time or another, have served to go bump in the night here in our town and surrounding environs. So, it is this year, and let me tell you until very recently I had quite the special Hallowe’en ghost story all planned out; a haunting little number about a tragic affair out in Denmark in the 1890s which, beyond untimely filling a couple graves, may have also left a mournful spirit wandering about near the Sandy Creek border, or so the story goes. I’ve had that piece waiting to share with readers since I first uncovered it last winter, although since July I’ve also had half a mind to instead share a piece on the old ‘half-haunted house’ of Chute’s Campground in Naples and its wonderful bedsheet ghosts who used to scare city-folk there in the 1920s.

And then there’s the old witchcraft legend connected with the wife of one of our earliest settlers… alas, so many fine tales to choose from, so few weeks in the spooky season of the year in which to tell them. I really was favoring the Sandy Creek ghost story for this year, honest!

But then, just a few weeks ago, I stumbled on an incredible piece of local history which after much consideration I have instead chosen to feature as this year’s Hallowe’en special. Rest assured, I will hold these other legends for future seasons (and perhaps tell a few in the meantime at the Bridgton Historical Society’s upcoming graveyard tour of the South High Street cemetery on Hallowe’en from 2 to 3:15, you’re welcome to attend).

Because the story I have for you today is the best kind of Hallowe’en treat; it’s both spooky, and true. It takes place right on Depot Street in the old Warren Walker woodshop just over a hundred years ago. Warren Walker was a brilliant man; he and his brother Asaph made furniture, phonograph players, even a steam automobile which if they’d have been quicker finishing might have beat out the Stanley Bros. for Maine’s premier steam car of the very late 1890s. They had the first gasoline engine in the village, they had the first electricity too, and their steam car is now in the State Museum, while a phonograph player is presently on display at our Historical Society courtesy of the Opie family.

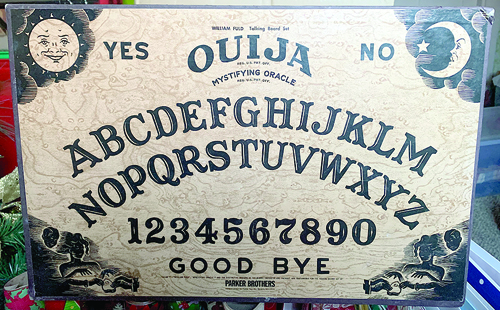

But a different piece of technology which Warren Walker made, which as yet no local museum has on display, is a certain kind of communication device which Mr. Walker diligently turned out for some fifteen years on contract with the William Fuld Manufacturing Company of Baltimore, Maryland. Of course, on the face of it, this was nothing new. He’d done contract work before; pipe stems had been a good sideline of his for many years — by the millions — and wooden whistles were also popular with out-of-state novelty companies. But in 1905, Mr. Fuld sent a wire inquiring if his shop was equipped to assist in the production of their new toy — a little something they’d been making since about 1890 called a, hold on, O… U… I… that’s right it spells ‘Ouija Board,’ I wonder if Walker knew just how significant his, and thus our town’s contribution to the burgeoning Spiritualist movement would become. Their first order was for 10,000 of the things, and Walker soon set about fabricating the necessary equipment to turn out the boards.

As we find from The Bridgton News of Sept. 14, 1951; “[Warren Walker] was always on the watch for opportunity and several times he scored. In the years before the First World War, the Ouija board craze hit America and most of the boards were made in the Walker Mill. Today’s generation never heard of the Ouija boards that their parents knew so well. The boards had the letters of the alphabet and a small wooden gadget on which a person rested their fingertips when using the board. The idea was that the player would ask questions. Then the gadget, presumably of its own volition, would move to spell out the ‘answer.’ Many a parent, wife, sweetheart, and child asked the board about the whereabouts and safety of American doughboys in World War I. Mr. Walker started out by making 10,000 of the boards for the man who invented Ouija and ended up by making a million of them before the craze ended in about 1920.”

Further details can be gleaned from the back stacks of local papers; from an article on Walker’s furniture shop appearing in Portland’s Evening Express of May 4, 1954, it is noted almost in passing how among other things, “Prior to World War I, he made Ouija boards for a Baltimore, Md. man who held the patent,” while from an interview which ran in the Lewiston Evening Journal of June 26, 1954, we learn from Walker himself how “for some 15 years he manufactured Ouija boards. How many readers recall these mysterious fortune tellers? He said he made as many as a million in one year, and that the number ran into the hundreds of thousands several years at the height of the Ouija board furor. Not only did he make them, but for several years he also tended to the printing on the boards.”

He kept at least five employees in this period, of whom we know the name of one; in the same news edition of Sept. 14, 1951, we also find the reminiscences of local boy-turned-man Joah Karter who briefly recalled his job working for Warren Walker in the 1910s, where among other duties he’d spent many hours “packing Ouija boards at the Walker Mill.” From the Vermont Journal of April 9, 1920, we learn that not only did they make Ouija boards proper, but also the necessary device now called a Planchette, but which were then called “Travelers,” being the little heart-shaped table which the hands of the operators, supposedly aided by the agency of the spirits, navigate around the letter board to spell out the answer to the question posed.

“Millions Want Ouija Boards. The pine trees of Maine contribute to the magic of the Ouija board, for in Bridgton a wood working shop is busy from morning till night making pine boards into the small table of the Ouija, called the traveler, on which the fingers rest when talking with the spirits. In fact, the peculiar charm of the Maine pine is communicated to the mystic, illusive quality of the Ouija and adds its part to the general fascination of this wonderful medium of the spirit world.

The last order of the shop is for half a million of the little travelers, five men besides the proprietor being employed, and for several years past the entire output of the shop has been the Ouija board travelers. The small, heart-shaped board and the three tiny legs are made by special machinery, which can turn out a great many in a day. The name Ouija has been printed on those previously made, but the latest design has a tiny glass inserted in the wood.”

Now, I don’t know about you but I find the notion that this little mill on Depot Street in Bridgton, where the American Legion hall is now, once put Bridgton on the map as one of the leading manufacturers of items that supposedly allow contact with the dead, to be more than a little surprising. Millions of these things — not rip-offs, but legitimate, name-brand Ouija boards — were made right here in Bridgton. That feels like the kind of thing which should have remained common knowledge. It’s a very interesting tidbit, and certainly the oddest item to be added to the list of local Bridgton manufactures. I never thought something would eclipse Knight’s Ammoniated Opodeldoc in terms of oddity, but ladies and gentlemen we may have just found it.

So now, the biggest question for me is… did they work? No wait, that’s not it. My biggest question, and possibly yours as well, should instead be, are there any of them still left in town? That’s a question I’ll have to leave for readers to answer. Of course, since Walker was making these on contract for the company that owned the trademarks to Ouija, none of the boards he made will have anything but the standard Ouija logo and Fuld company patents. They won’t say Bridgton on them. But it stands to reason that if one could find an antique, authentic Ouija board of the vintage of say 1910 or so, with the little heart-shaped planchette on its three felt-bottomed dowel legs, it would almost certainly be one of the uncounted millions once turned out right here just a stone’s throw from the Historical Society on Gibbs Avenue, all thanks to the diligent craft of Warren Walker. Personally, I’d like to see one someday.

If you happen to find one, and put me and an original Bridgton Ouija board in a room together, and shut the door on Hallowe’en night, I just might come out of there with a brand-new ghost story to tell… courtesy of Mr. Walker himself! Then, I’d really have something for next Hallowe’en’s column.

Till next time!